Indigenous Science of Time

GPE – Correlation

Geraldine Patrick Encina (GPE), a cross-disciplinary researcher with Mapuche and Celtic ancestry has recovered indigenous knowledge on time that has been misinterpreted and overlooked by Western scholarship for five centuries.

This new correlation proves and reaffirms indigenous principles and knowledge about time-space and cycles of sky, earth, ecosystems, communities and families.

Western conceptions of time have always perceived a unidirectional flow into a distant future with no end.

Whereas Indigenous conceptions of time describe time as cyclical, meaning there is an apparent “return to the beginning”. This makes prior and present cycles become models of what lies ahead.

In this short presentation we will walk you through the original Mayan and Mesoamerican calendar system, and explain the reason why, for the past five hundred years, it has been interpreted by Western scholars as being incorrect.

First, it is important to understand that all calendar systems were based on the Sun’s movement across the horizon.

Historically, Mesoamerican timekeepers perceived time by watching the cyclic movement of the Sun along the landscape horizon, which they marked as a tropical year.

A tropical year, also known as a solar year, represents the time taken by the Earth to complete one revolution around the Sun. It is well known among astronomers that this cycle takes almost 365 and 1/4 day.

Towards 600 BC the Olmec civilization was creating the cultural foundations for the Maya the emerge, and most importantly, it put the Year Calendar in place. The first day of the year was August 13th. This day was chosen for its precise alignment of the sun over the top of the pyramid. . It is 145 days after the March Equinox and 40 days before the September Equinox. Many of the Mayan pyramids are aligned to August 13th and to the equinoxes.

The Julian year calendar was 365 and ¼ days long. It was intended to approximate the tropical (solar) year, which is 11minutes shorter than that. So, the 11 extra minutes per year resulted in the building up of a full day every 128 years.

As a result, the Julian version of the calendar year becomes three days longer every four centuries compared to observed equinox times and the seasons. By the fifteen hundreds, there were ten days too much, which pushed the calendar’s date March 21 ten days away from its Equinox position.

This discrepancy was corrected by the Gregorian reform of 1582. The Gregorian calendar has the same months and month lengths as the Julian calendar, but manages to avoid the building up of the excess three days by eliminating the leap days on years evenly divisible by 100 and inserting leap days only on ends of centuries that are multiple of 400.

To make their calendar work, Pope Gregory XIII issued an edict that now made Oct 4th into October 14th.

The Maya built their pyramids to mark precise movements of the Sun.

On August 13 the Sun is right in the middle of the sky at noon on one of the oldest Mayan areas. On this single day a perfect square cross alignment can be obtained in relation to the sunrise, noon, sunset and midnight. This captures the time space conception of the very core of Mesoamerican civilization.

This astronomical event is what identifies the first day of the New Year for the Mayan.

The GPE Correlation, confirmed by two contemporary Mayan Achi timekeepers in Guatemala, invites understanding through the Sun Cycle Circuit (SCC) – an indigenous perception that values and recognizes the Sun’s journey through a complete day cycle, which includes sunrise, noon, sunset and midnight days! By honoring the movement of the Sun through each of these Sun Cycles – an entire awareness of the Sun’s presence is accounted for, even at night! Western scholarship only considers the beginning of a full day cycle at midnight and therefore does not have a conception of days starting alternatively at sunrise, noon, sunset or midnight

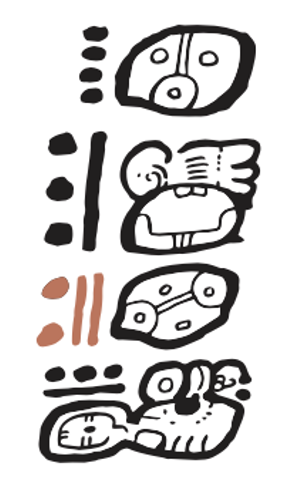

The Western study of Mayan timekeeping does not acknowledge the role of the Year Bearers, who have been depicted in many epigraphic and iconographic Mesoamerican contexts. For centuries these Year Bearers, have been overlooked and ignored. Their role has not been fully understood until now.

This immensely important role has been misunderstood since the early fifteen hundreds by western scholarship, Missing out the whole point of the Year Bearer’s work was what actually led Western scholars to declare since the very beginning of Colonization that the Mayan Year calendar lagged off because it didn’t include or account for the quarter day at the end of each calendar year.

Indigenous Timekeepers did not need to implement a leap year because they understood that each Year Bearer performs the passage of the last quarter-day by means of their cardinal shifting, passing on the haab, the new year, to the next Year Bearer.

Each of the four Year Bearers works for an entire year cycle, day by day, or k’in by k’in. In the east, the Kaban Year Bearer counts Sunrise days. In the north, the Ik Year Bearer reckons the Noon days. In the west, Manik Year Bearer keeps track of Sunset days and in the south, Eb Year Bearer counts midnight days. One by one, each Year Bearer performs the task of ritually passing the haab (the year) to the next Year Bearer, which is thus brought to life.

In the east, the Kaban Year Bearer keeps track of every sunrise for 365 days. Then, he ritually passes the haab (the year) to the Ik Year Bearer in the north. This ritual helps include the 1/4 passing of a day but only as ceremonial time.

In the north, the Ik Year Bearer keeps track of every new day beginning at noon for 365 kins (or noon days). Once the year cycle is completed he ritually passes the haab (the year) to Manik Year Bearer. Again this ritual is acknowledged as absorbing 1/4 passing of the day in ceremonial time.

In his turn, the Manik Year Bearer accounts for each new day from sunset in the west. After 365 kins (or sunset days), he ritually passes on the haab (new year) to Eb Year Bearer in the South. Again 1/4 day of ritual time is included with the passing.

The Eb Year Bearer accounts for 365 kins or (midnight days). His ritually passing of the haab (the year) to Kaban includes the ritual 1/4 day.

So after four years of the same Year Bearer rituals, there totals one full ritual day. A full four-year cycle begins once again, and this goes on and on until a Bak’tun cycle is completed. This is a good time for Year Bearers to enter a thirteen-year period of rest.

The Western conception of time that has days beginning forever at midnight, imposed the leap days upon the Mayan calendar so to include those four quarter days that were apparently missing.

But the Mayans and Mesoamerican people had figured out another system, based on the ritual work of the four Year Bearers.

The quarter days appeared to be missing precisely because they were ritual time. This is what Western scholars could never figure out.

The Mayan calendar does not need to include a leap year every four years because it accounts for every last 1/4 day in ritual time and helps “push” the starting of the day cycle further ahead so to correct its solar alignment upon the fourth year.

This is why it’s so important for contemporary Mayan daykeepers to understand that they must NOT employ the leap day, February 29th . There is no need for the Mayan day that is destined to name the Sun of March 1st to stay behind to name February 29th.

By imposing the Western Calendar on Mayan daykeeping the date of any ceremony or festival keeps staying behind in relation to the solar year cycle – creating a chasm between what the calendar says about the movement of celestial bodies and the unfolding of life on Earth and what the Sun and animals and plants are actually up to.

The inability to comprehend or unwillingness to respect the role of the Year Bearers has interfered with the measuring system of k’ins (days) on the Long Count used by Olmec and, later, Mayan astronomers. This misunderstanding has not only a distorted concept of the Long Count but has also misrepresented the beginning of Creation calculated by Olmecs and narrated by Mayans.

By freeing the K’in (day) at the end of every fourth year from being a leap day, the Long Count that expresses 13 Bak’tun and which holds 1,872,000 (one million eight hundred and seventy two thousand) k’ins which totals more than 5,128 years instead of the conventional 5,125 years.

So many k’in (days) freed from being a leap day represent over 3 years in the 13 Bak’tun cycle, and allow to see that there were astronomical cycles involved within that big cycle.

All this explains why the starting date calculated by Mayan scholars missed the significant astronomical event of Venus and the Moon.

The predominance of Venus and Moon in the painted Mayan books helped Dr. Patrick Encina infer that 8 Kumku of Creation day must be related to an important astronomical event in which Venus and Moon were significantly implicated. The introductory passage on page 51a of the Dresden Codex describes Venus (Lamat) rising out of the water after 8 days since Creation. Coba stela 1 tells that, on 8 Kumku, Moon was Waning crescent and so it follows that Moon rose on the West 8 days later.

From an astronomical standpoint, it was understood by indigenous timekeepers that once Venus and the Moon return to their staring point on Creation day – the 13 Bakt’un cycle would be completed.

The description of Venus and Moon under the water at the starting of 13 Baktun means that they were also under the water at the closing of the cycle.

On May 3rd 2013 the Moon and Venus completed their cycle marking the actual closing of the Long Count 13 Bak’tun cycle. Western scholarship, based on erroneous calculations, proposed that Dec 21st 2012 was the end of the Mayan Long Count Calendar.

Going back 5,128 years to the beginning of Creation, Dr Patrick Encina identified the ideal Venus-Moon configuration, which happened on 3117 BC on July 27th. Again, this date is in direct conflict with western scholarship, which calculates creation starting on Aug 11th 3114 BC even if it has absolutely no astronomical relation to what we are told in the Mayan texts.

The fact is that this astronomical event of the moon and venus aligning again not only reconciles Creation time but more significantly, proves that Mesoamerican timekeepers were accurate and precise centuries ahead of their time.

Mesoamerican timekeepers kept meticulous notes to demonstrate a cosmology, knowledge and ontology that was the very foundation of their science.

The GPE Correlation affirms the time space conception as presented in Mesoamerican philosophy, which conceives a universe that is in perfect cyclic motion.

The consequences of the gross oversight undermines of such precise calculations of alignments with cycles of the universe are devastating — to say the least. Hundreds of Mayan communities lost track of their days, months, seasons and festivities. The orderly world-vision and the traditional devices to follow cycles were displaced by poor replica that gave them the illusion that their calendar had never been lost –when regrettably, it had.

With the recovery of the original versions of the Mayan calendars, communities have the great task of remembering, recovering and practicing the traditional ways of timekeeping and doing timely ceremonies.

The alignment of the celestial bodies in relationship to life on Earth is a concept that is honored, recognized and regarded by many indigenous communities across the world today.

Dr. Patrick Encina’s research has huge ramifications for indigenous peoples that seek alignment between celestial bodies, life ON earth and ceremonies.